Age Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive eye disease that affects the macula—the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision. AMD is one of the leading causes of vision loss in people over 50, gradually impairing tasks such as reading, recognising faces, and driving. Although it rarely causes complete blindness, the impact on quality of life can be significant.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of AMD is multifactorial. Age is the strongest risk factor, with prevalence increasing sharply after age 60. Genetics also plays a major role; individuals with a family history of AMD, especially those carrying variants of the CFH and ARMS2 genes, have a substantially higher risk. Environmental and lifestyle factors contribute as well. Smoking is the most significant modifiable risk factor, doubling the chances of developing AMD. Other associated risks include high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and prolonged UV exposure. Light-coloured irides and a diet low in antioxidants are also believed to increase susceptibility.

Types of AMD

AMD is classified into two main forms: dry (atrophic) and wet (neovascular). Dry AMD is the more common form, characterised by the accumulation of drusen—yellow deposits under the retina—and gradual thinning of the macula. Vision loss is typically slow. Wet AMD, although less common, can cause sudden vision impairment. It occurs when abnormal blood vessels grow beneath the macula and leak fluid or blood, causing rapid and often profound vision distortion.

Diagnostic Imaging

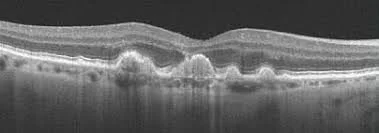

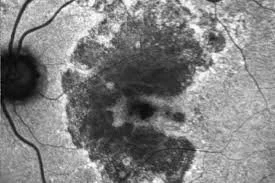

Modern imaging technologies are essential for diagnosing and monitoring AMD. Retinal photography (top image) documents the appearance of the macula, enabling baseline comparison and long-term monitoring of drusen and pigmentary changes. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) (middle image) provides high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina, allowing clinicians to detect fluid, retinal thinning, drusen, and structural changes with precision. Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) (bottom image) highlights metabolic activity of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Areas of increased or decreased autofluorescence can signal early disease activity or impending geographic atrophy, making FAF particularly useful in dry AMD.

Treatment

While there is currently no cure for dry AMD, nutritional supplementation (the AREDS2 formula) can slow progression in moderate disease. Lifestyle modifications—stopping smoking, maintaining a healthy diet rich in leafy greens and omega-3s, managing systemic health, and using UV protection—are strongly recommended. For wet AMD, anti-VEGF injections remain the gold standard, targeting the abnormal blood vessel growth that drives the disease. These injections, administered every few weeks to months, can stabilise vision and often improve it. Emerging therapies, including longer-acting agents and gene-based treatments, are expanding future possibilities.

With early detection and modern treatment options, many individuals with AMD can maintain functional vision and quality of life.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) demonstrating large drusen (raised white clumps) in the deeper layers of the retina

Fundus auto-fluorescence demonstrating geographic atrophy (black areas)